Ninjas & Knights – A Systems Perspective on Design Practice

![]() Navigate this presentation using the arrow keys on your keyboard or by swiping left or right on your mobile device.

Navigate this presentation using the arrow keys on your keyboard or by swiping left or right on your mobile device.

This is a ~25-minute talk I shared with members of the fabulous Amsterdam UX community on February 6, 2019. Thanks to Tatiana and Dave for organizing the event and thanks to User Intelligence for being such generous and gracious hosts. Oh, and thanks to everyone whose copyright I'm violating with this slide deck. Please don't sue me.

To set expectations appropriately, this talk is broad and philosophical so you won't be leaving here with any new tactical skills or techniques. I do hope you’ll leave just a little wiser, with a bit broader perspective on the work we do and the growing power and responsibility we have as designers and creative thinkers.

I’m going to begin with a personal story that got me thinking about design a little differently.

Like a lot of Americans, I'm kinda into cars. When I lived in the US, I drove a 1973 BMW which I found quite beautiful and incredibly fun to drive.

Now that I live here in Amsterdam, I drive something even more fun but I still really appreciate a great car.

So, when we needed to go pick up our adorable new Border Terrier puppy from a breeder in the East of the country, We decided to rent a car.

I thought it might be fun to rent the modern version of my old BMW. Of course, after 45 years of iteration, the family resemblance had faded.

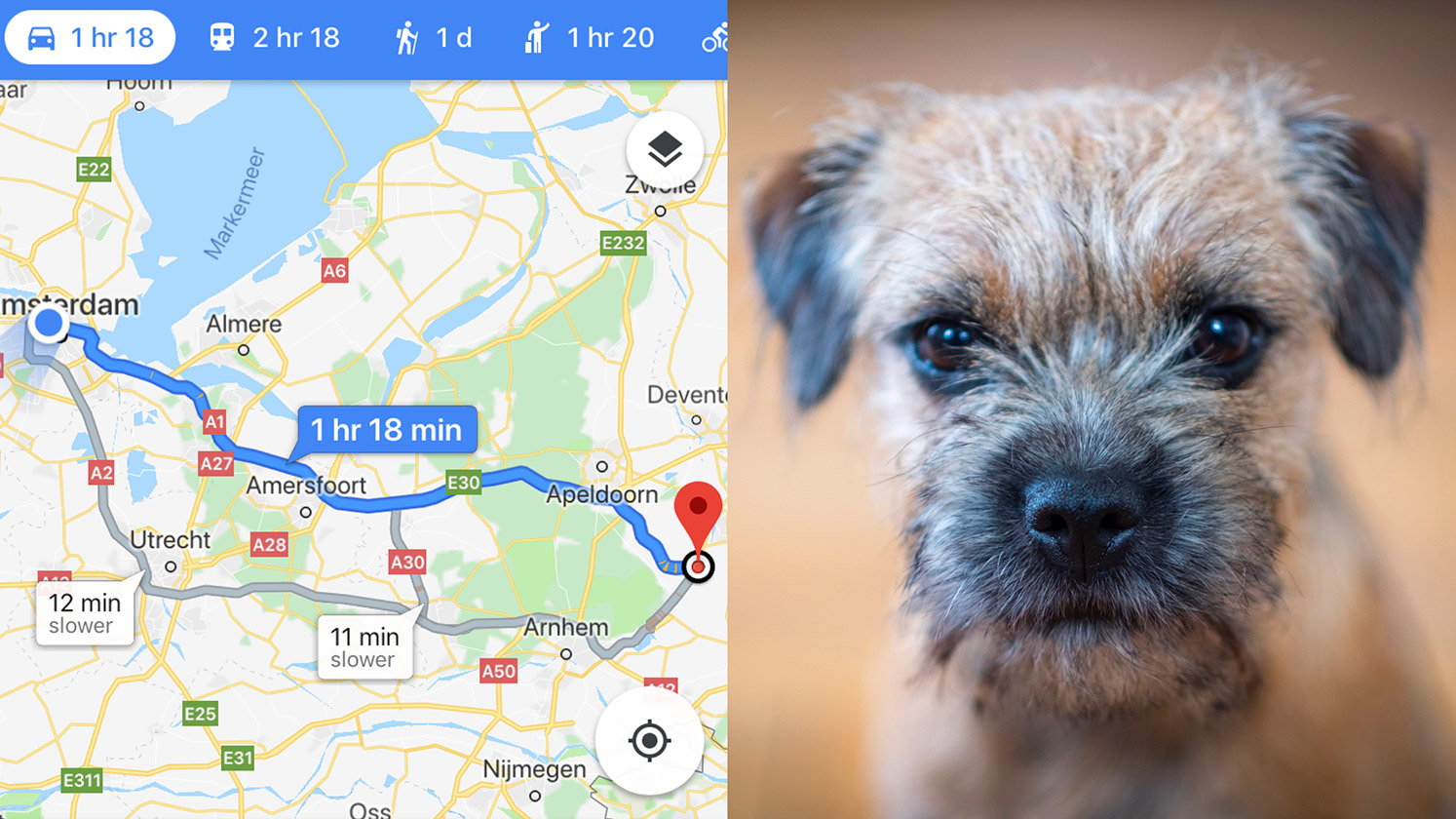

When I went to pick it up, I was pretty disappointed. I wondered where that lean, teutonic, German-ness had gone.

To my eye, this thing looked like the offspring of a puffer fish and seriously ANY… other… modern… car. Those are all different models on the right, by the way.

It was clear that over time, my beautiful motor car had morphed into a bland transportation solution, the product of thousands of small decisions without much of an aesthetic vision tying them together.

Apparently somewhere along the way, a wind tunnel had blown it’s soul away.

But beauty is in the eye of the beholder so I suspended my judgement and went to the data.

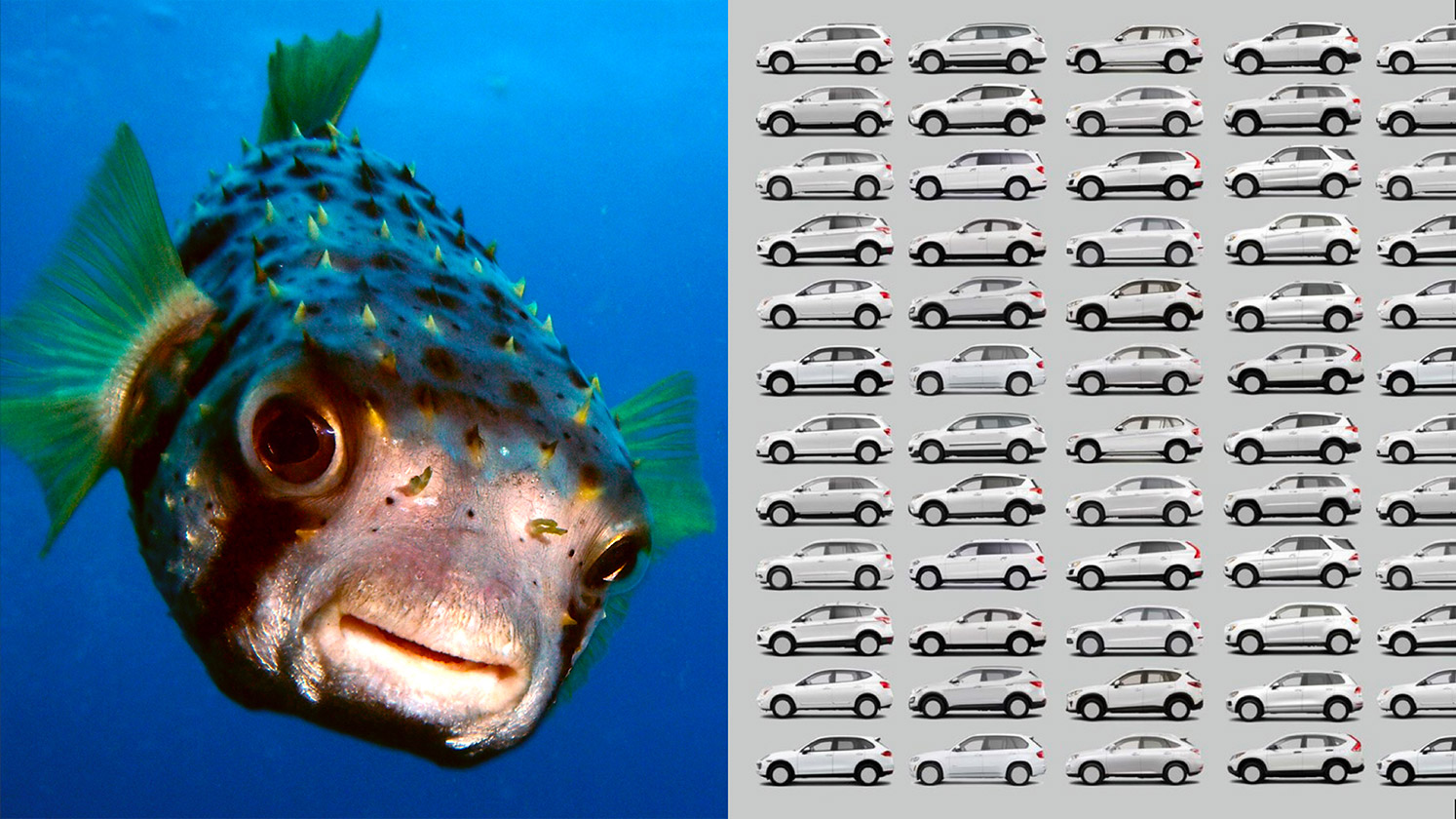

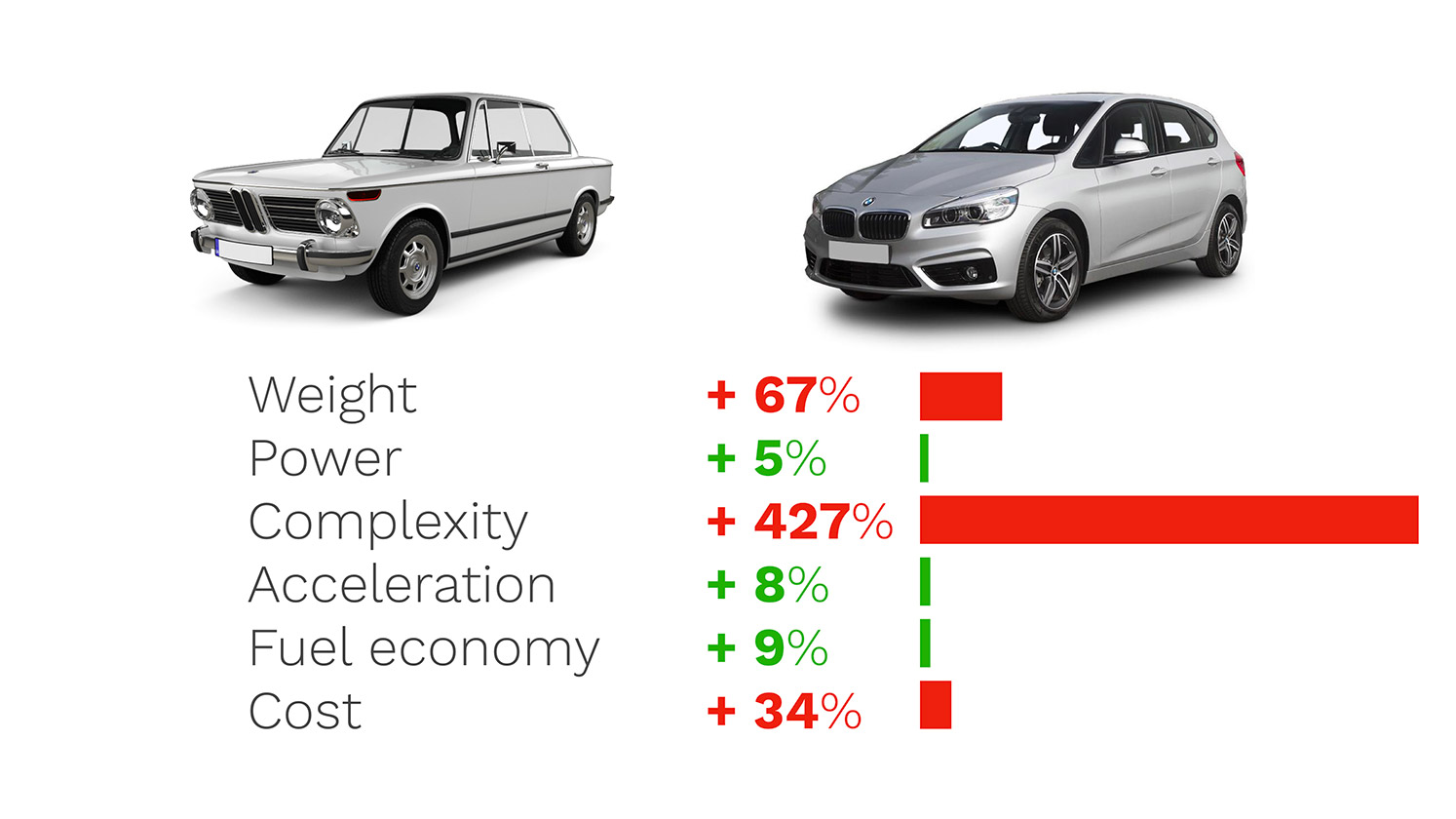

I discovered that the new car is 600kg heavier and made from over 4 times as many individual parts. It’s also over 1/3 more expensive, adjusted for inflation, meaning a person making an average salary needs to work about an extra month and a half to buy it.

Another stat that I don’t show here is that it’s 21% bigger on the outside but 17% smaller inside which makes no intuitive sense.

Ok, so it’s slightly quicker and more fuel efficient than it’s ancestor but I expected a LOT more from almost half a century of iterative, market-driven refinement.

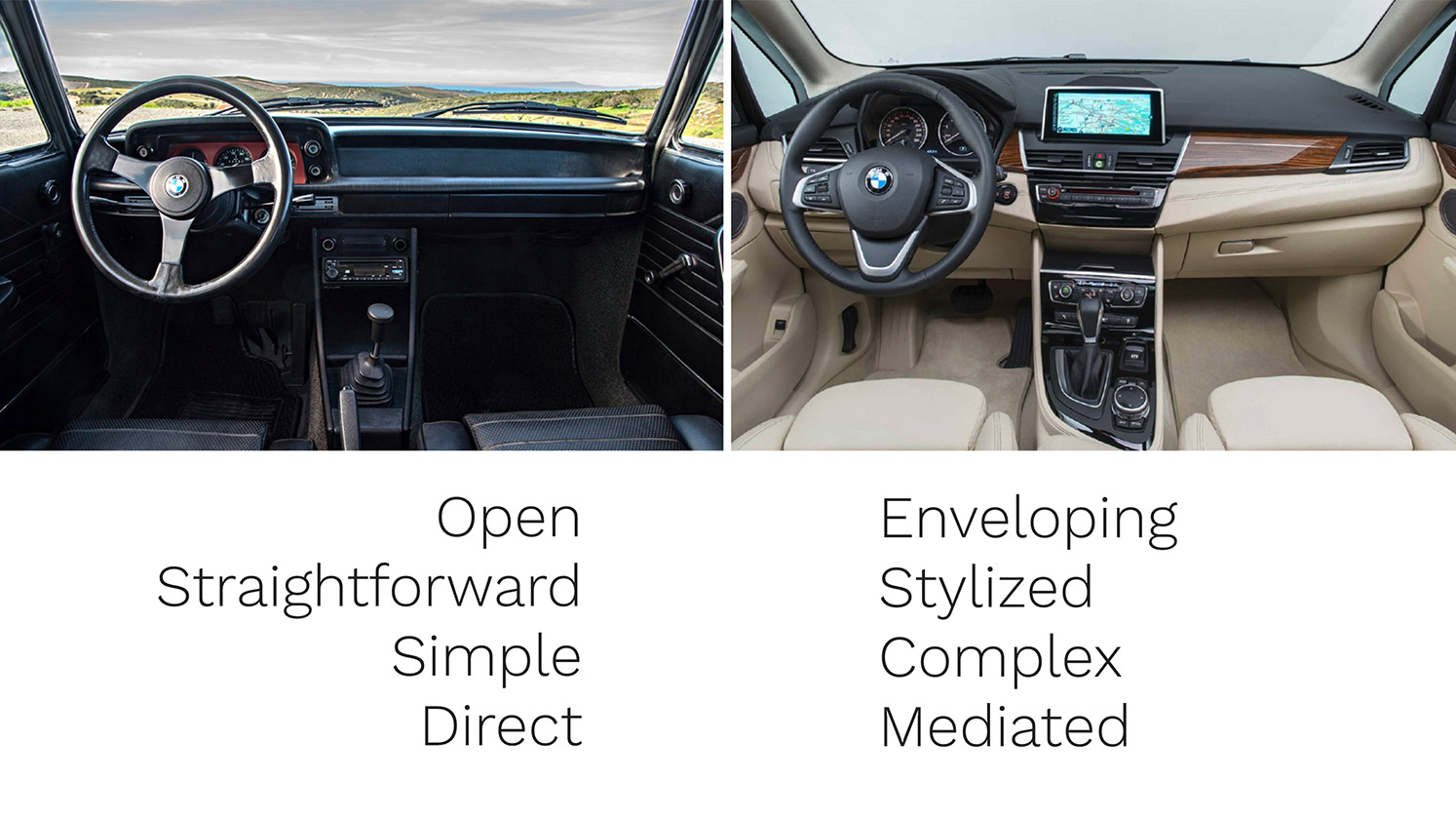

I thought “Maybe the answers are inside. Maybe the driving experience is so much better that I can overlook the puffer fish aesthetic.”

I climbed in and almost had a claustrophobic panic attack. I hadn’t stepped into a car, I had put a car on. I was isolated in a deep, thick capsule of technology and airbags. I could barely see over the dashboard and I’m not a short guy.

By comparison, the new car felt like a heavy, cumbersome suit of armor.

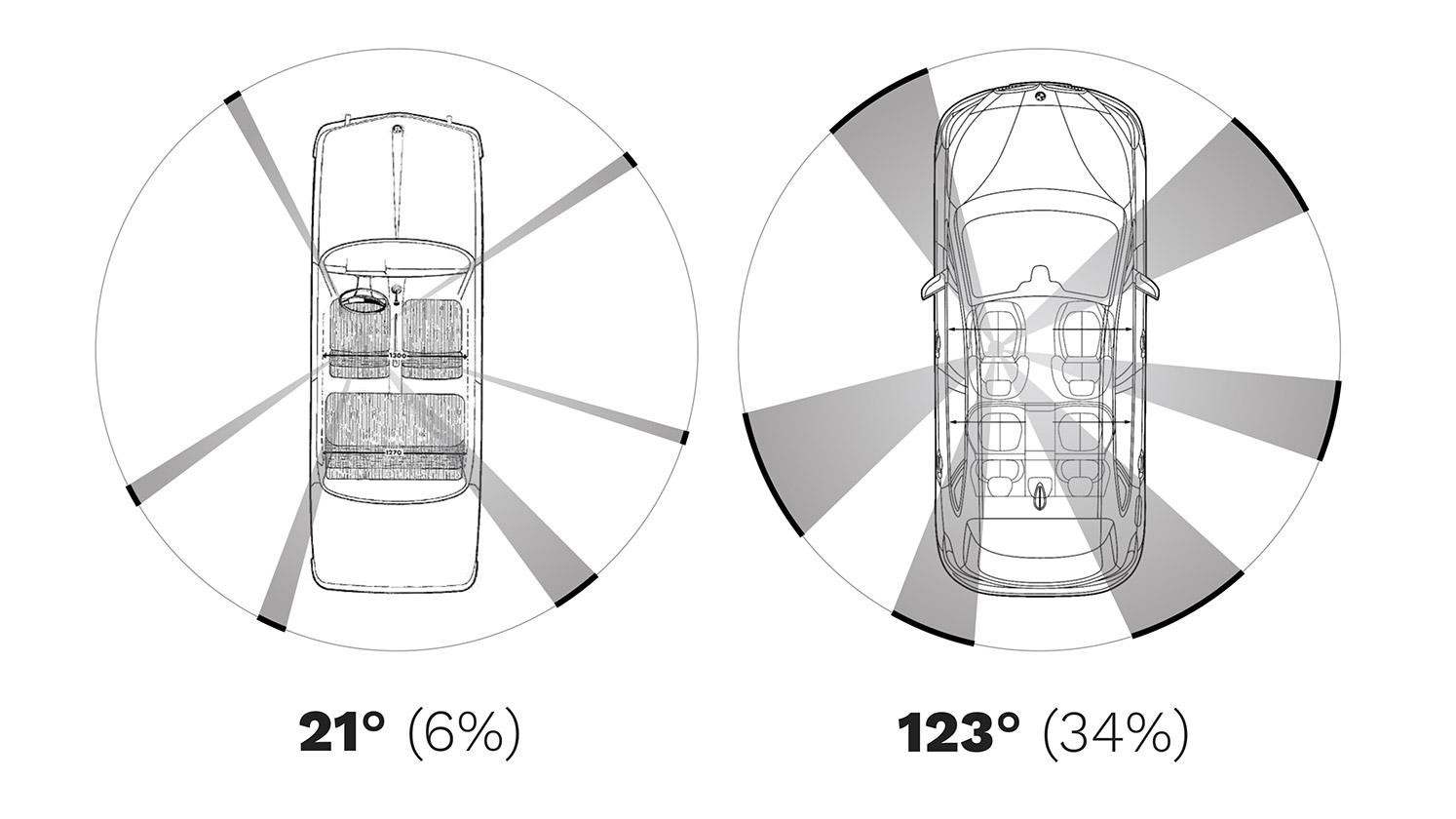

And, just like with a suit of armor, I couldn’t see much of the world outside.

These blind spot diagrams illustrate the dramatic difference. The new car has a whopping 123 degrees of total obstruction, nearly 6 times as much as grandpa.

Oh, and most of the glass that did remain was darkly tinted.

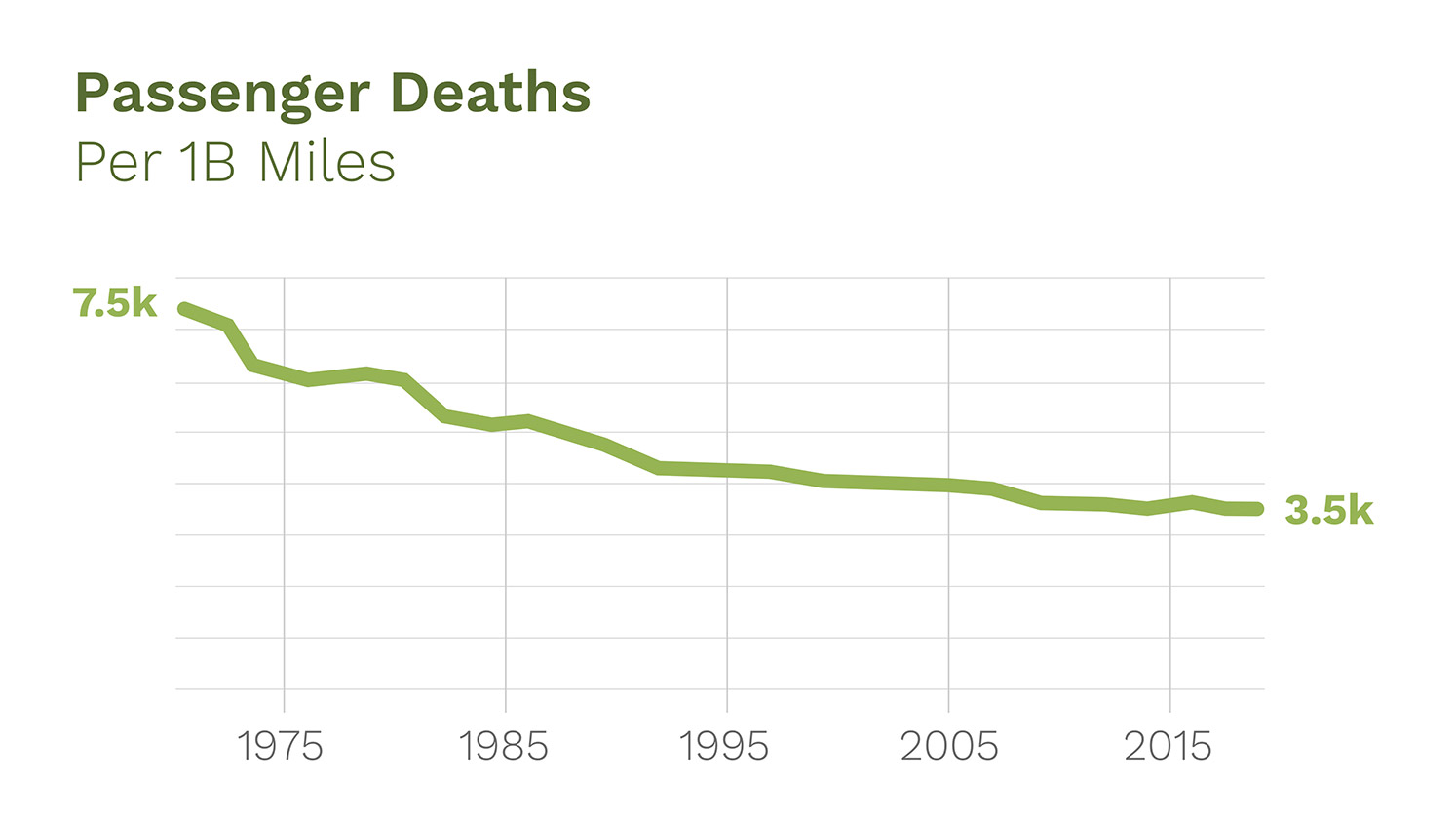

Of course, the auto industry has made huge progress in safety so, next time I’m in a high speed crash, I hope I'm in a modern car.

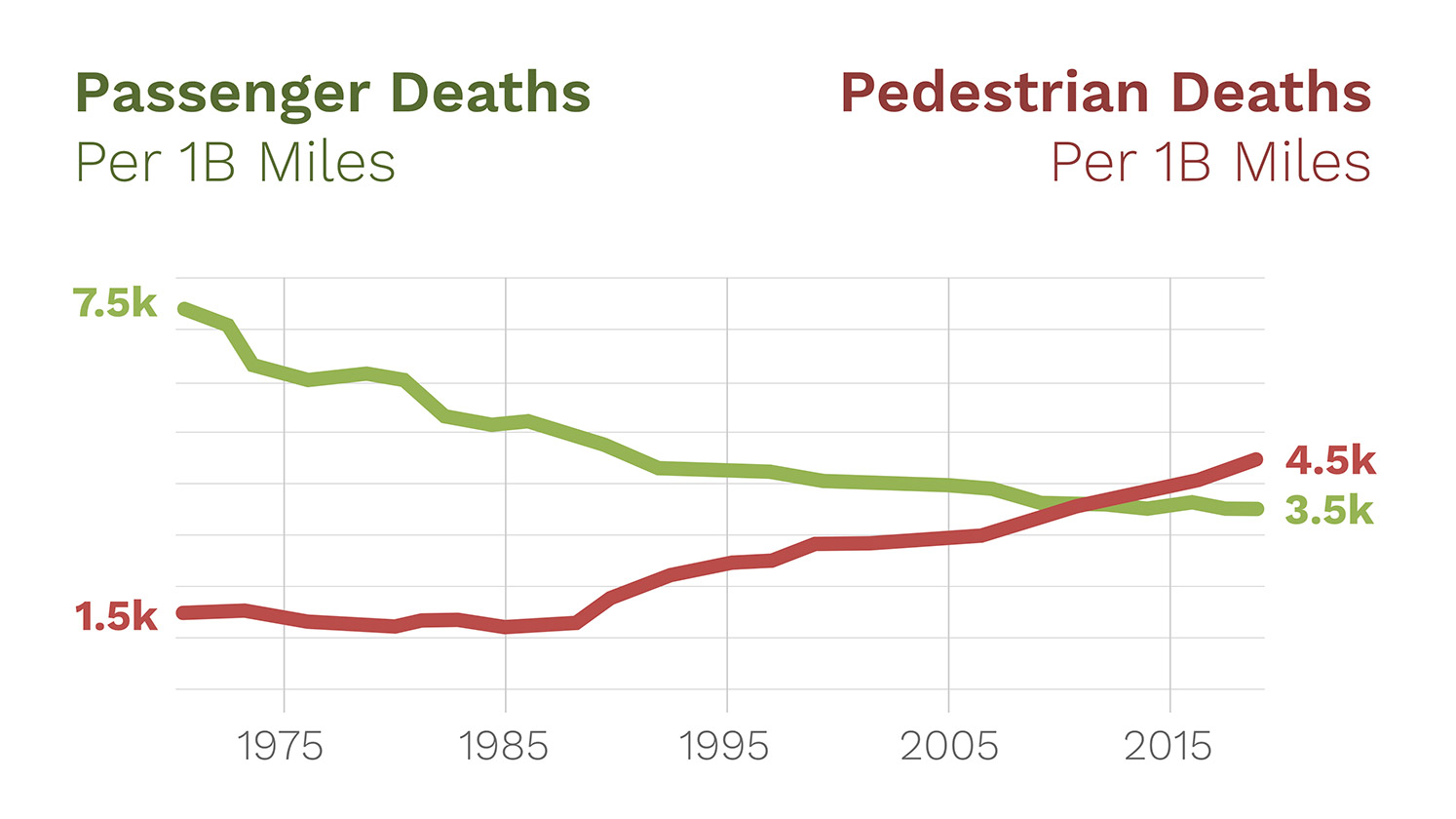

You’re less than half as likely to die in a car now than you were 45 years ago. Impressive progress.

Unfortunately, if you’re not in a car, you’re about 3 times more likely to be killed by one. Auto safety researchers cite a lack of visibility as the leading factor in this increase.

So, while these 4 decades of "improvements" are saving about 4000 passengers a year, they're having the unintended consequence of killing about 3,000 pedestrians and cyclists.

These numbers are North America only, by the way.

It was my experience with these two cars that inspired the title of this talk. My old car seemed like a light, nimble little ninja and the new one felt like a big, clunky knight.

The job to be done hadn’t really changed over time but something about the underlying approach certainly had.

A ninja’s approach is pretty straightforward. He does his job efficiently and still has time for dinner with Mrs. ninja the kids.

The knight, on the other hand, has a really long day ahead of him. He needs to deal with his armor, his horse, his squire, the prayers, the king, the princess, and more.

On top of all that, he’s highly vulnerable to disruptive change, like, I dunno, gunpowder?

The big question in my mind at this point was WHY did my ninja BMW morph into a knight BMW over those 4 decades?

To begin to answer that, I think we need a little perspective.

One tool I’ve found useful for gaining perspective is called Oblique Strategies. It was created back in the 1970s by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt as a deck of cards.

They’re still very cool and yes, it's available for iOS, Android, and on the Web.

One of the cards in that deck really stuck with me. It just says “Zoom out.”

Now, whenever I’m wrestling with a problem or a concept, I have this habit of zooming out, way out so bear with me as we go back in time for a minute in search of answers.

Just in case we haven’t all read Sapiens yet, here’s a quick synopsis:

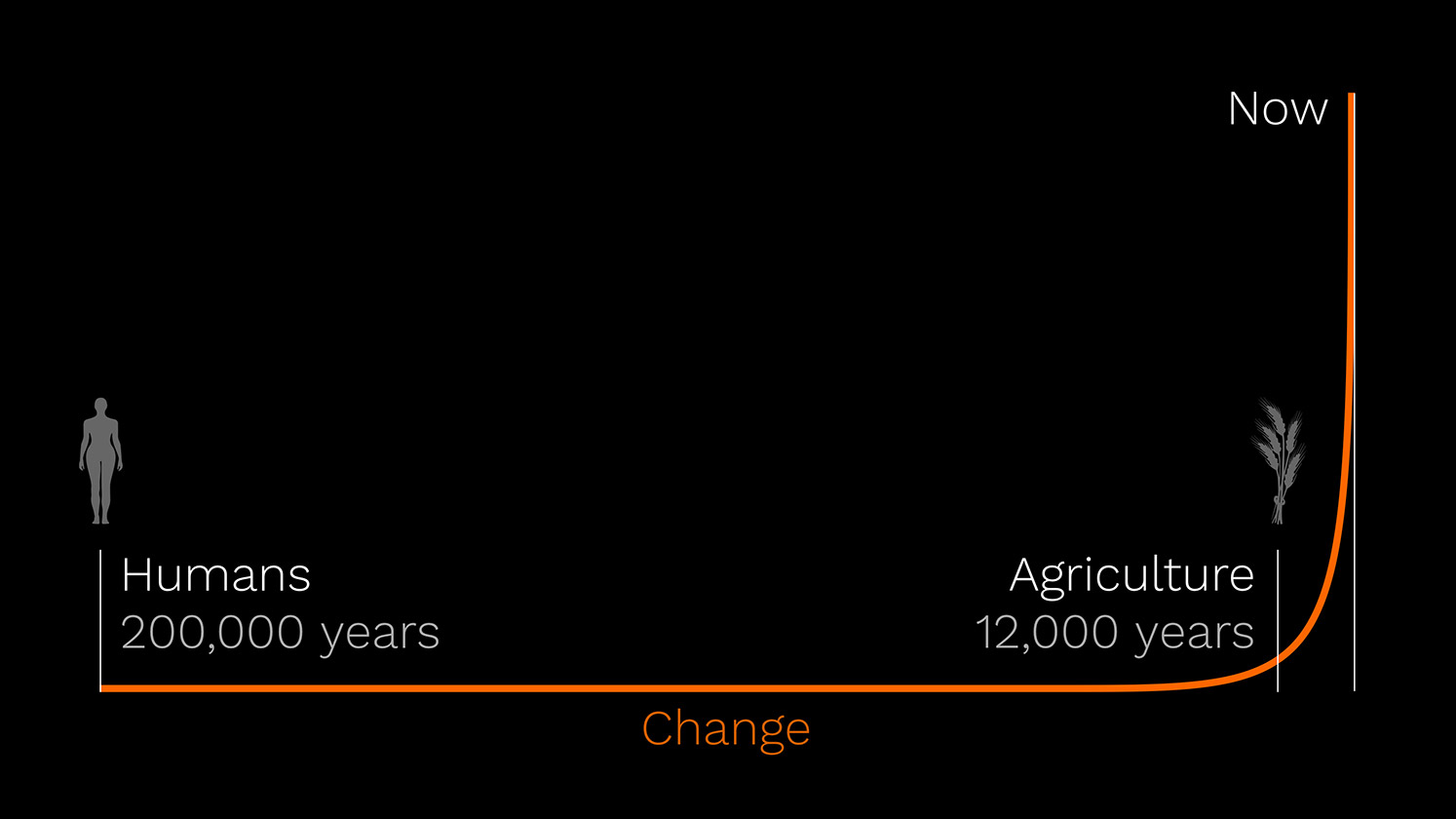

We modern humans came on the scene about 200,000 years ago, give or take. Same bodies, same brains, worse teeth.

On this time scale, agriculture is a pretty recent innovation.

But farming enabled us to stay put, stay fed, make more babies, and develop specialized skills like dentistry. Bad teeth problem solved!

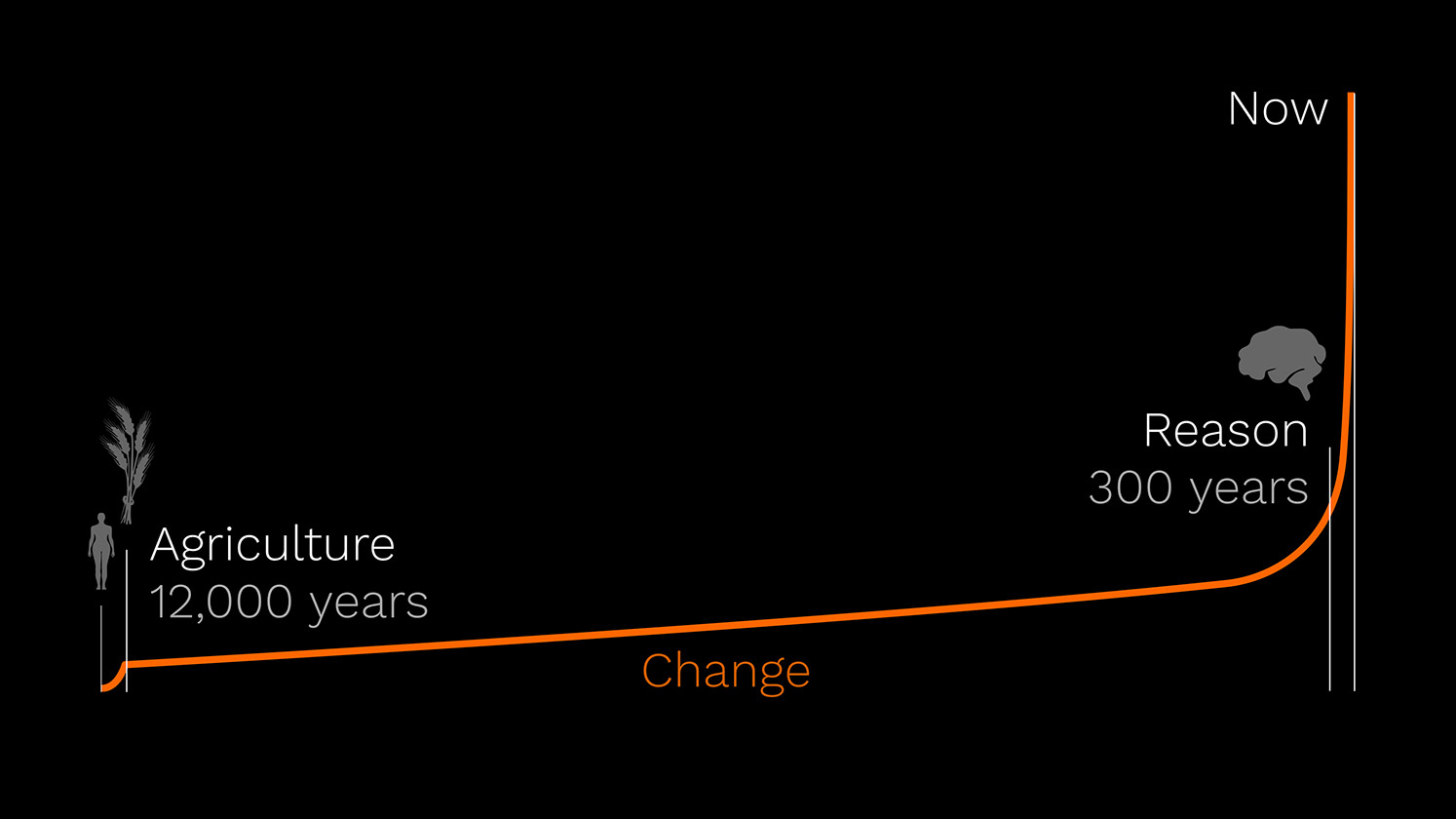

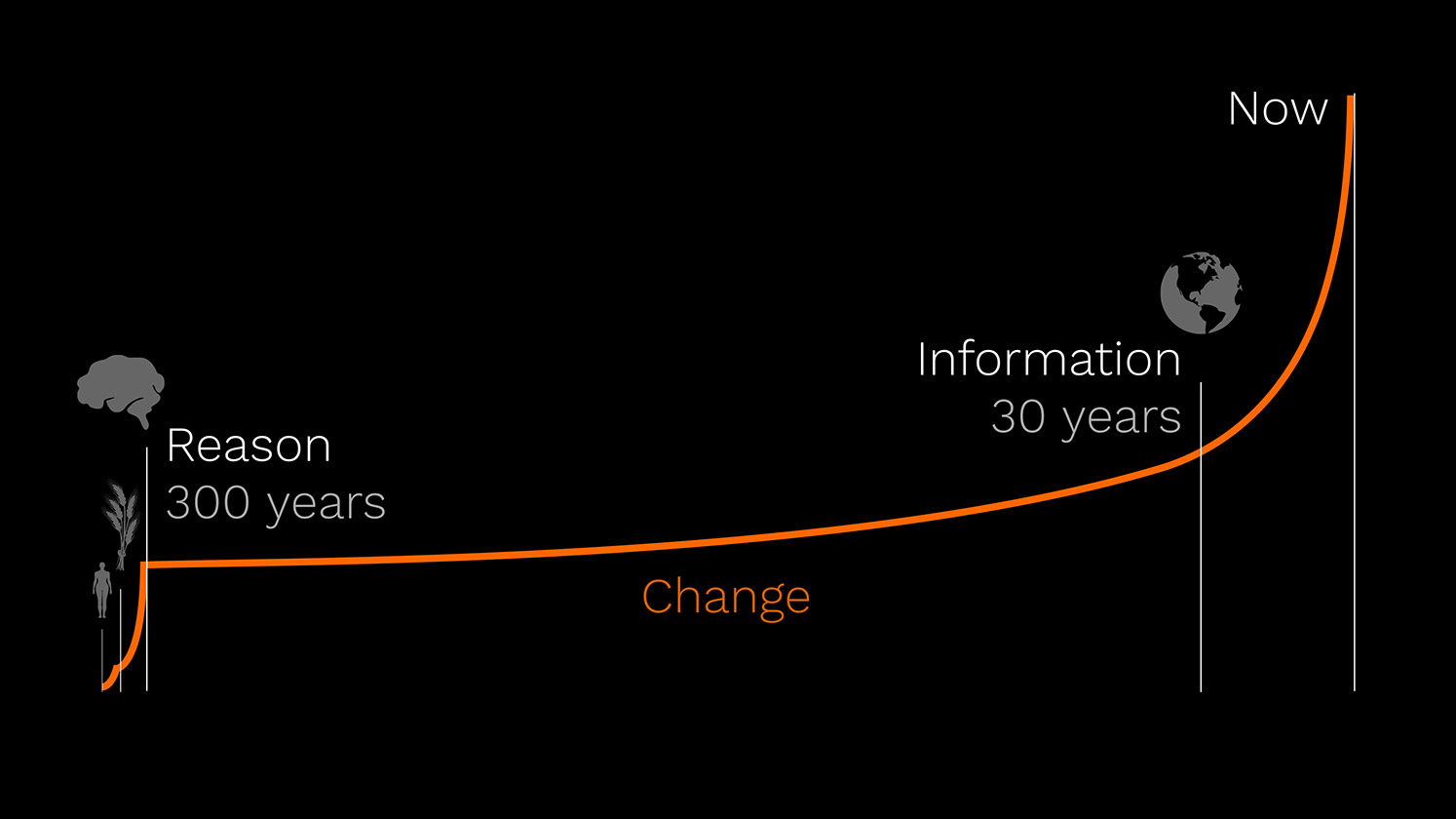

Then, very recently came the Age of Reason. In this last 300-year blink of an eye, we developed a shit ton of scientific knowledge and a global material economy. Pretty much the whole culture we know.

The point I’m making here is that biologically and cognitively, our species is still adapted to horizontal times but almost instantly, our times have gone vertical. Kurzweil, intuitive linear, exponential progress yada yada.

Which is why we hear silicon valley futurists using the words hockey stick as a verb. “Alexa is going to seriously hockey stick in 2019.”

Now, I promised this talk would be philosophical so meet René Descartes, rockstar philosopher and mathematician of the 17th century. That was back when philosophy and mathematics were kinda the same thing.

In some ways, we can think of Descartes as the father of the hockey stick.

Here’s a fun fact: He lived right here in the neighborhood, right by the Anne Frank House, about 400 meters from where we’re sitting right now.

Descartes introduced a hugely disruptive idea about nature…

…the world…

…and the cosmos.

He used the clock as one of his central metaphors for nature, the mind, and everything really. By taking apart the “clock” and examining its pieces, we could understand how the whole thing worked.

This rational, atomic view of the world gave rise to the radical idea that we could master nature and bend it to our will.

If you missed it at University and feel like starting down this very deep rabbit hole, I recommend Descartes’ Rules for the Direction of the Mind which I think is a fantastic title for a book.

Some people have called this “book zero” of the enlightenment.

This idea went viral. It quickly displaced the holistic but superstitious and ineffective thought system of the dark ages.

The rest is history. Descartes’ clock, or “mechanism” quickly became the world’s dominant system of thought because, y’know, science fucking works!

So far, this thought system has produced modern civilization,…

…the industrial revolution,…

…transportation networks,…

…cheap, plentiful food,…

…and LOTS of pretty happy people,…

…7.7 billion of us and counting. Incidentally, that’s a little over twice as many as when I was born which kinda blows my mind.

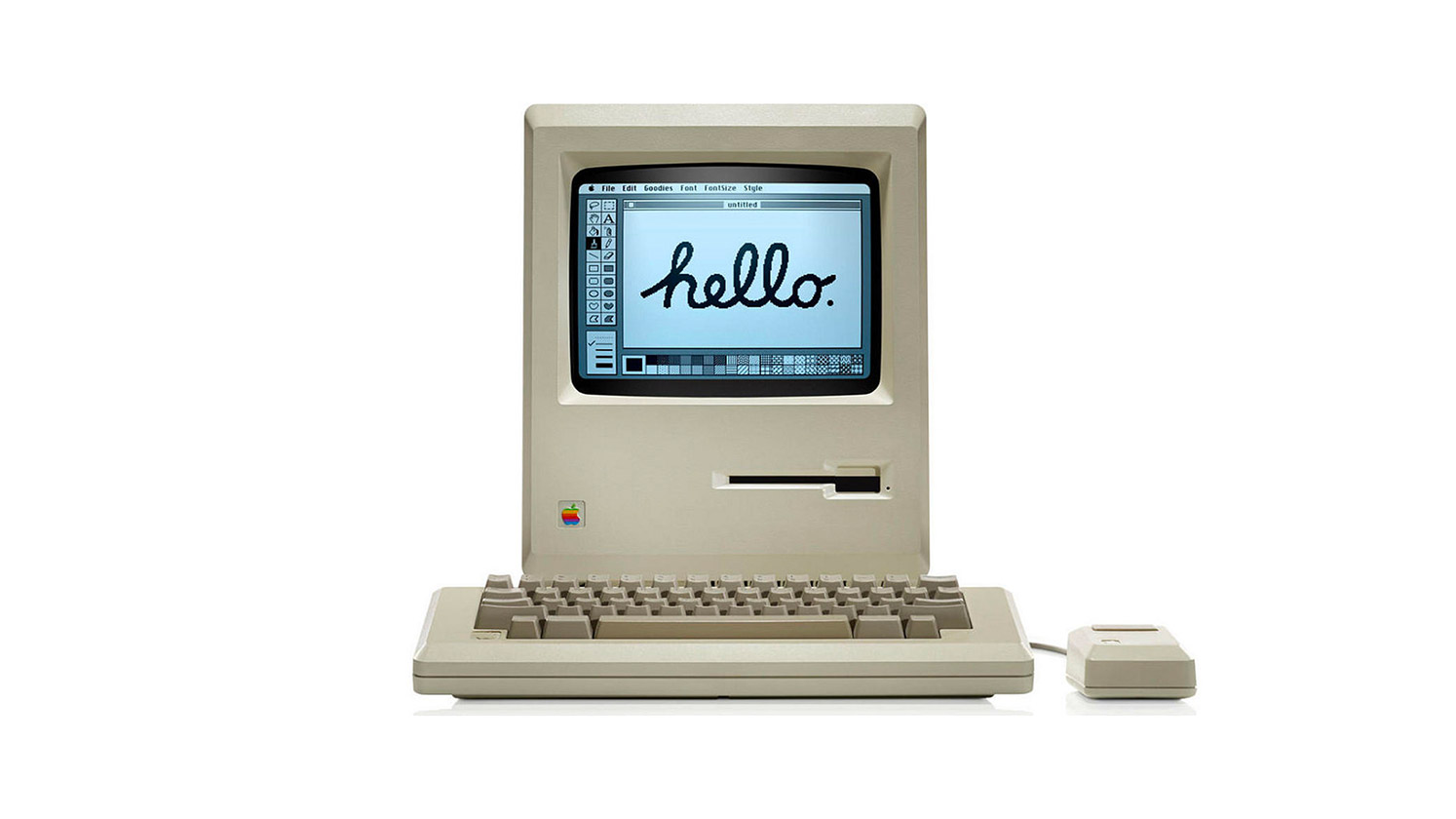

Then, sometime yesterday afternoon, we used our Cartesian mastery and specialization to create this friendly little fellow,...

...and the internet (For the kids in the audience, that’s a dial-up modem. Google it),...

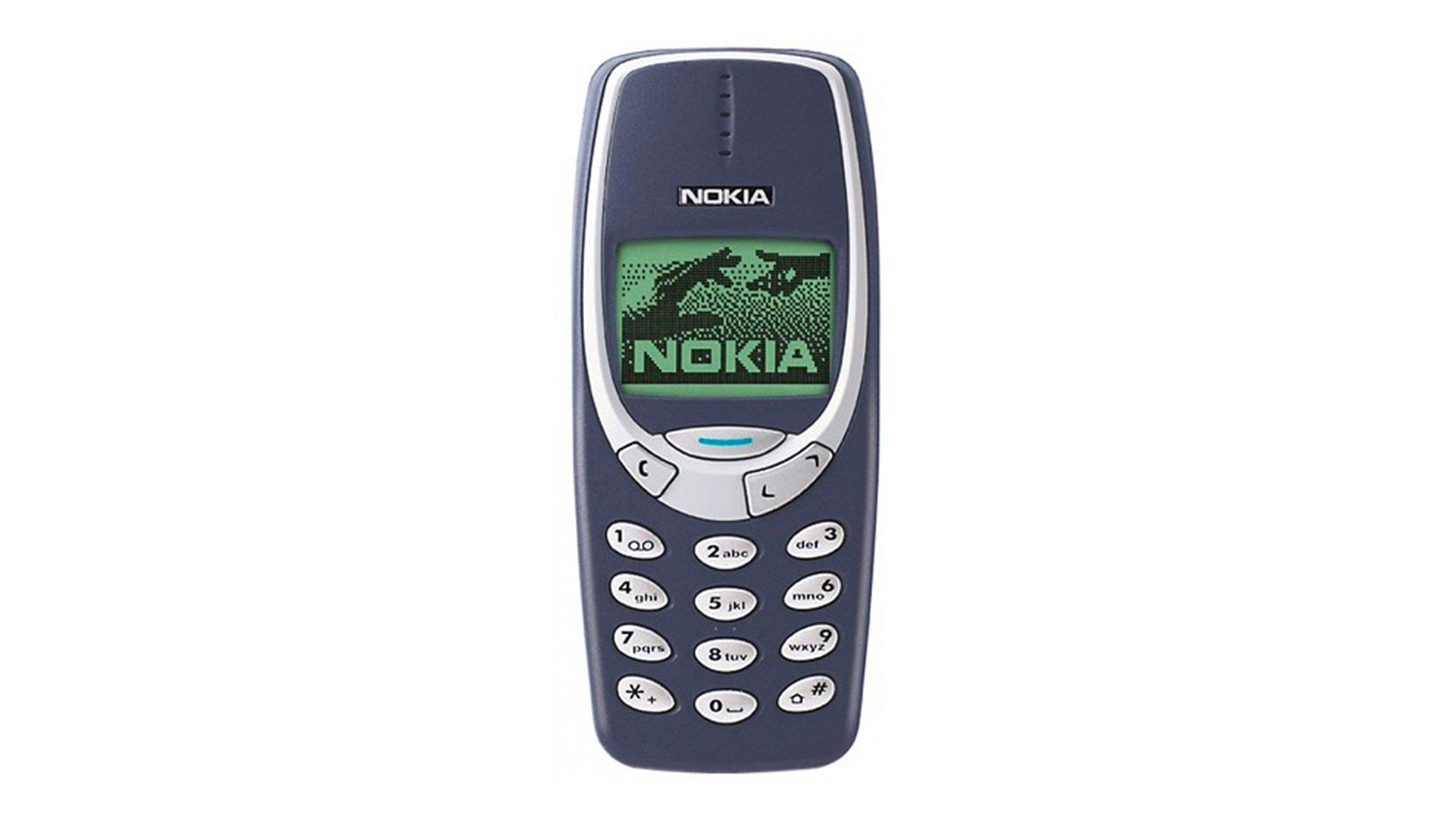

...mobile phones,...

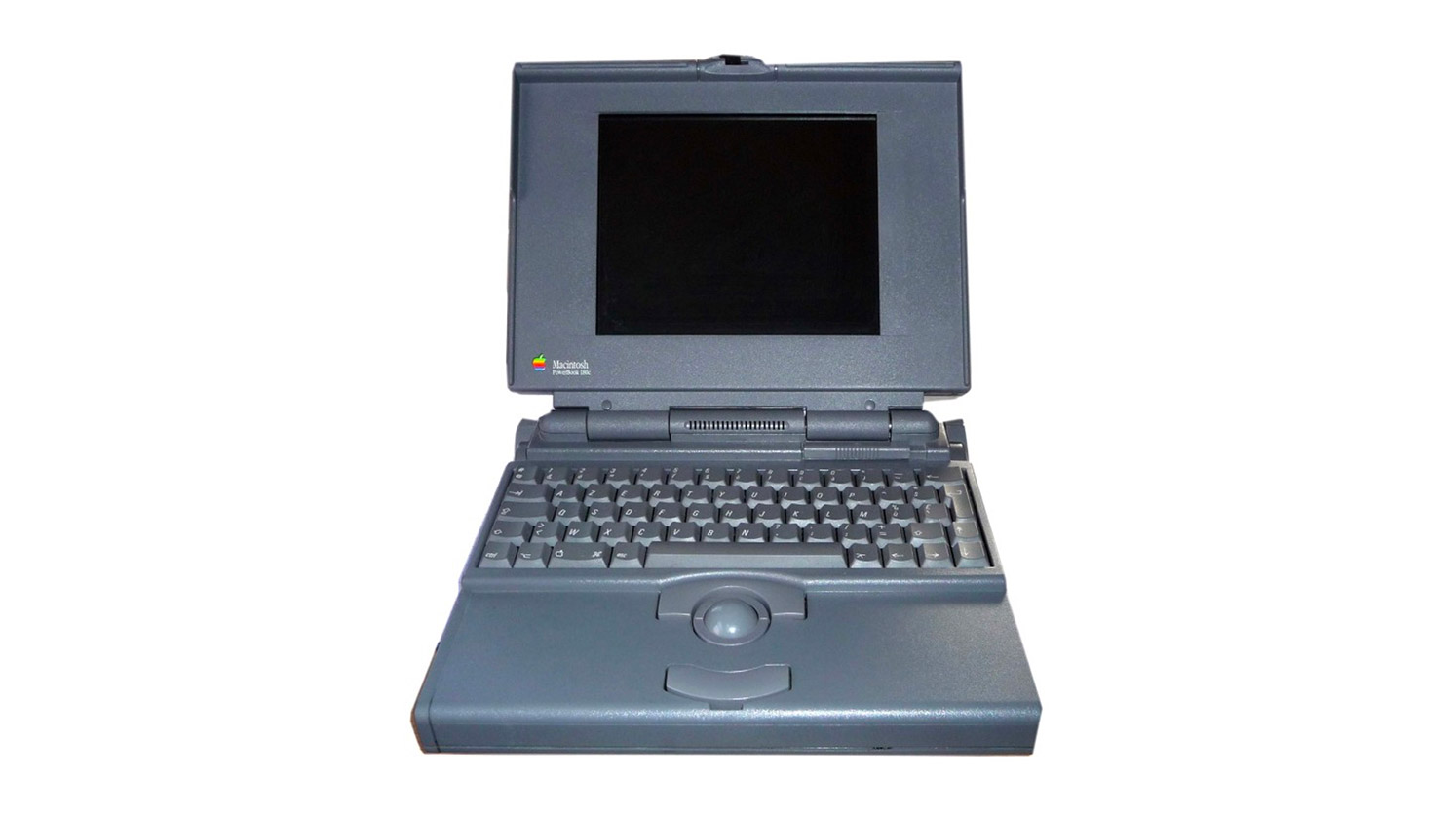

…laptops (I actually had one of these which was about 1/4000th as powerful as the phone in my pocket),…

…smaller mobile phones,…

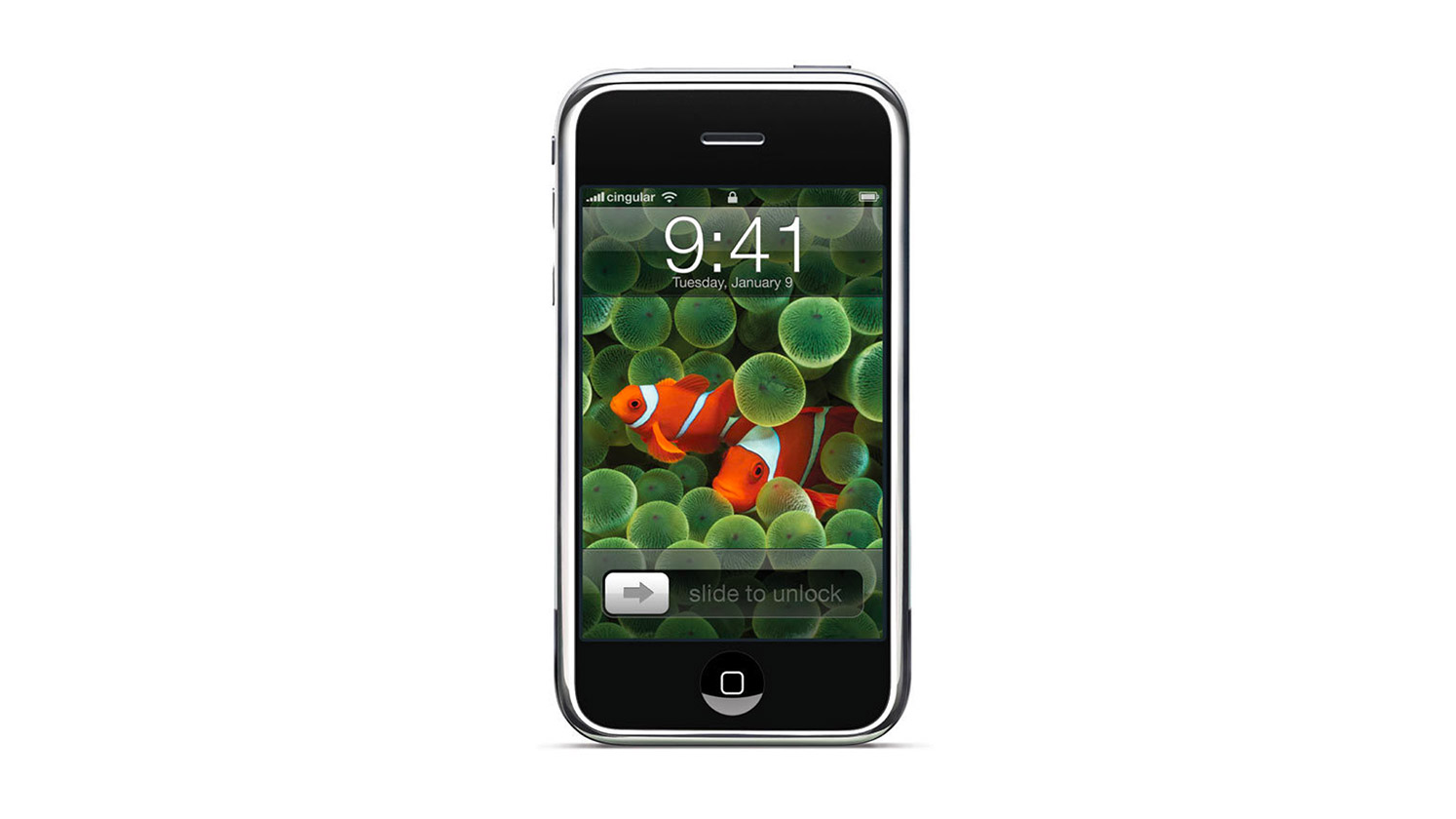

…touch screens,…

…the cloud,…

…apps,…

…voice assistants,…

…IoT devices,…

…VR,…

…better computers,…

…better phones,…

…machine learning and AI,…

…wearables for people who don’t mind being creepy and unattractive, also known as early adopters,…

…and wearables for the rest of us.

Before all this progress makes us too dizzy, it seems healthy to step back and remind ourselves that philosophically, Descartes’ old clock is still ticking away at the center of all these innovations.

After nearly 4 centuries of success, that mechanistic Cartesian mindset is baked deep into our culture but it’s starting to crack under the scale, complexity and pace of the challenges we face in the modern age.

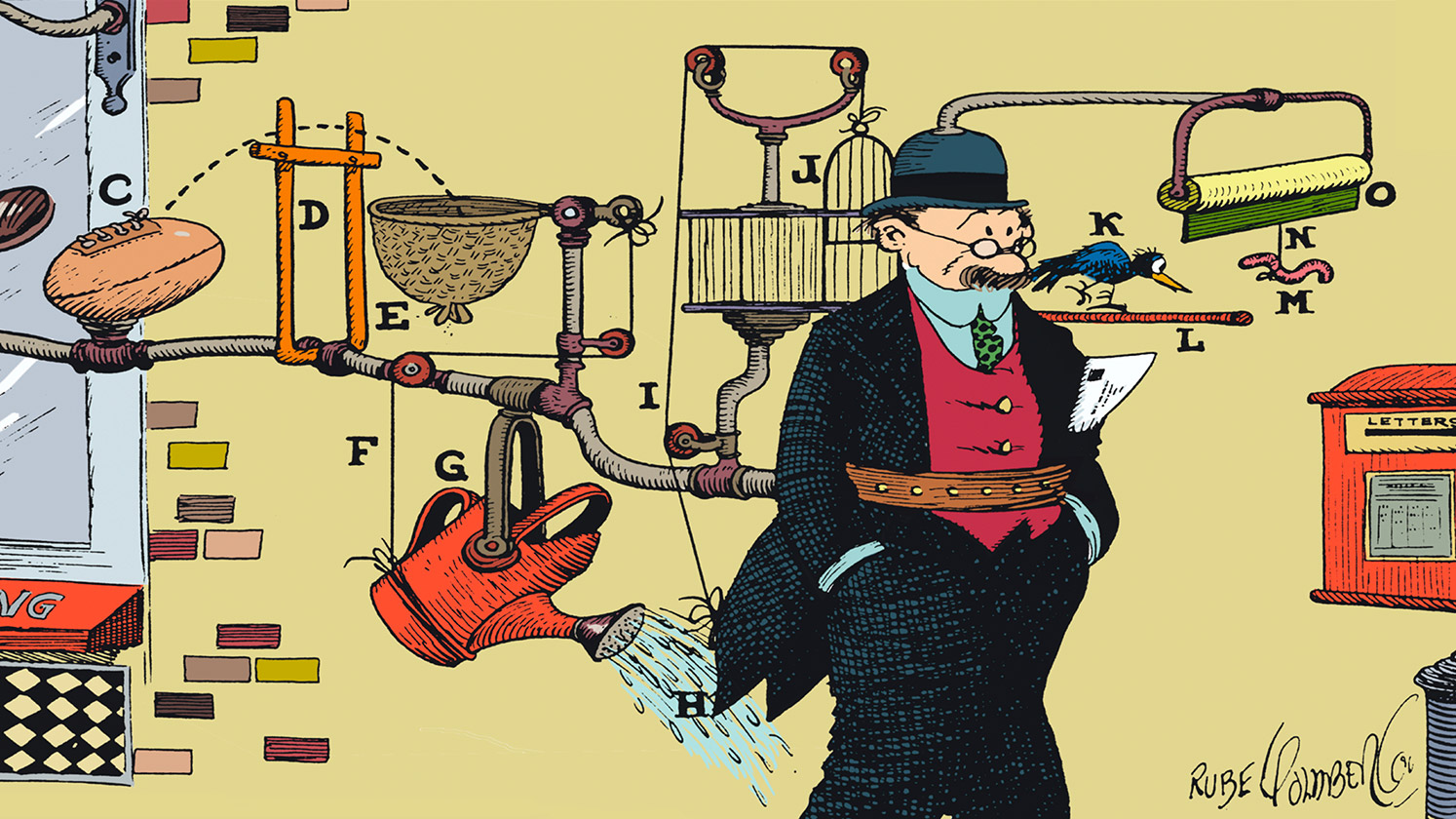

Behold, The Homer! It’s simply the manifestation of Homer Simpson’s automotive feature wish list. I think The Homer does a great job of illustrating the consequences of focusing on individual features with little regard to what they add up to.

I think we’ve all been involved with Homer products but even if we get everything “right” at the product level or even the service level, chances are the larger system that product inhabits is still a Homer.

Descartes’ clock has served us well, but as things really start to hockey stick, our mindset needs to evolve beyond the local, incremental, and short-term. We need to get good at practicing design at higher levels.

To borrow the boiling frog metaphor, the heat is on. Will we jump in time?

To use another deliberately environmental metaphor, Will we make the leap from focusing on individual trees to the more holistic, systems-level work of managing forests?

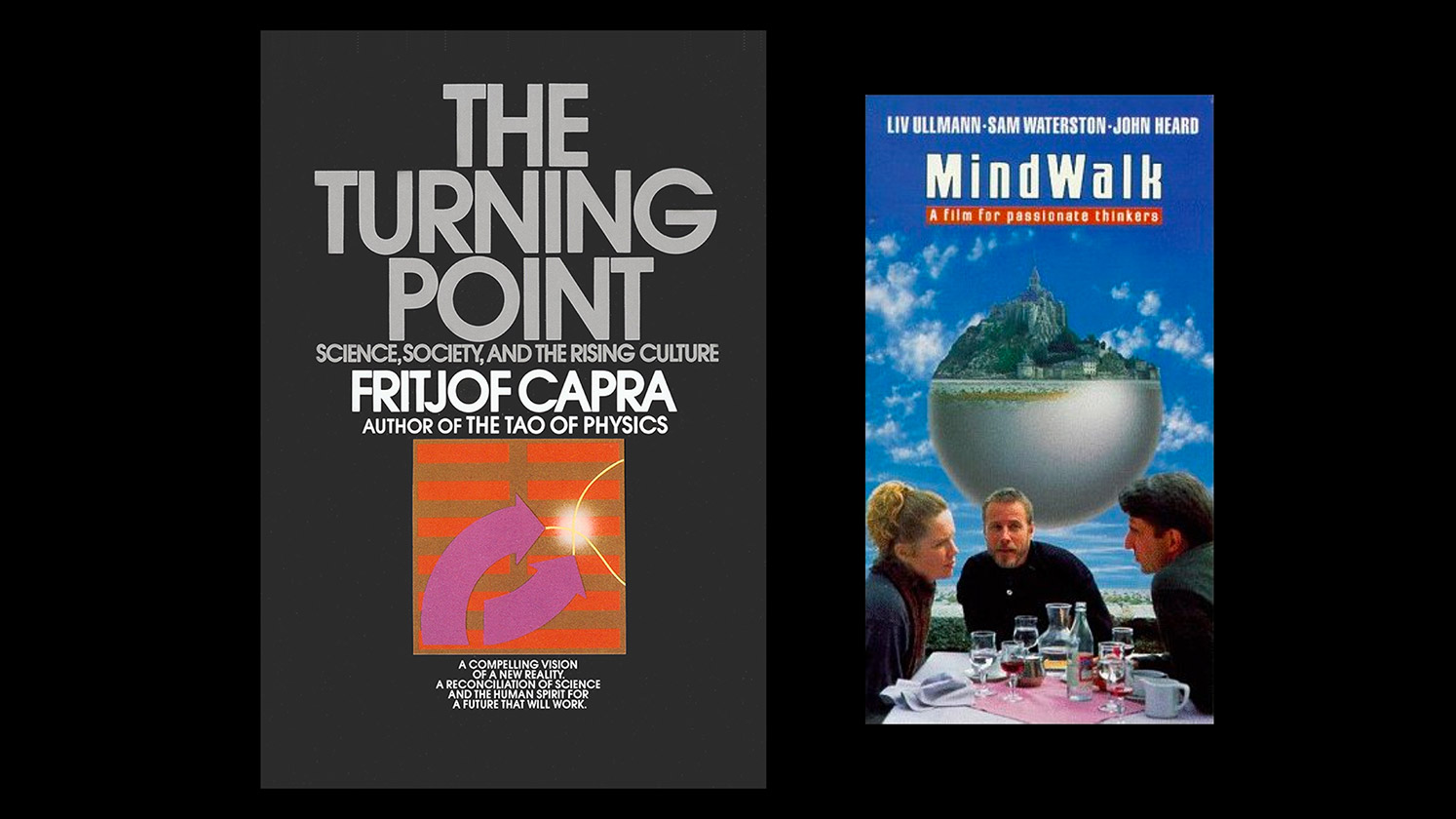

Fritjof Capra, who wrote the Tao of Physics, goes mind-bendingly deep on this shit in his brilliant book, The Turning Point.

It was adapted as the 1990 non-blockbuster, MindWalk. If you can seriously focus your brain for a couple hours and overlook some dated styling, I highly recommend this film. The whole thing is free on YouTube.

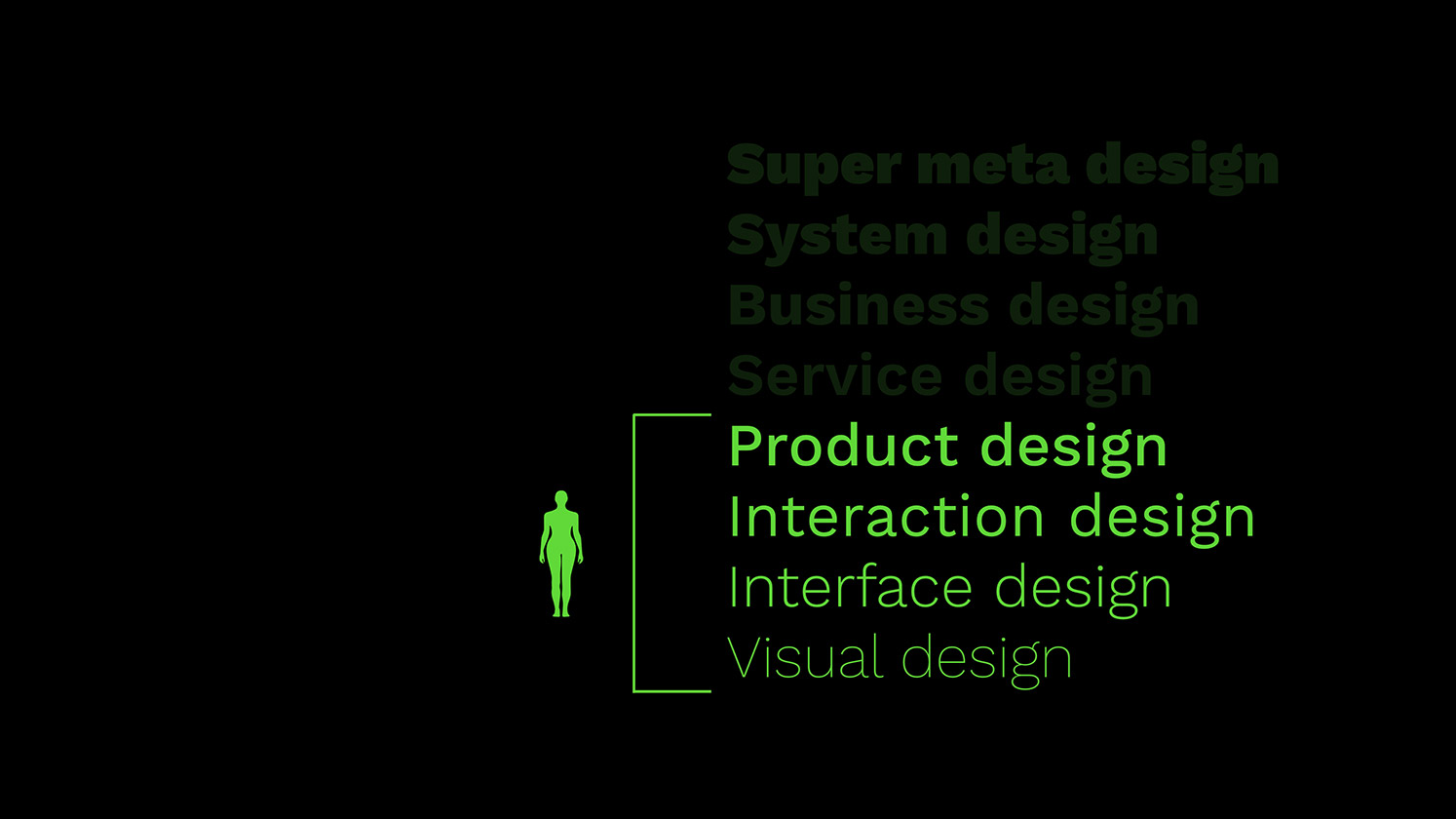

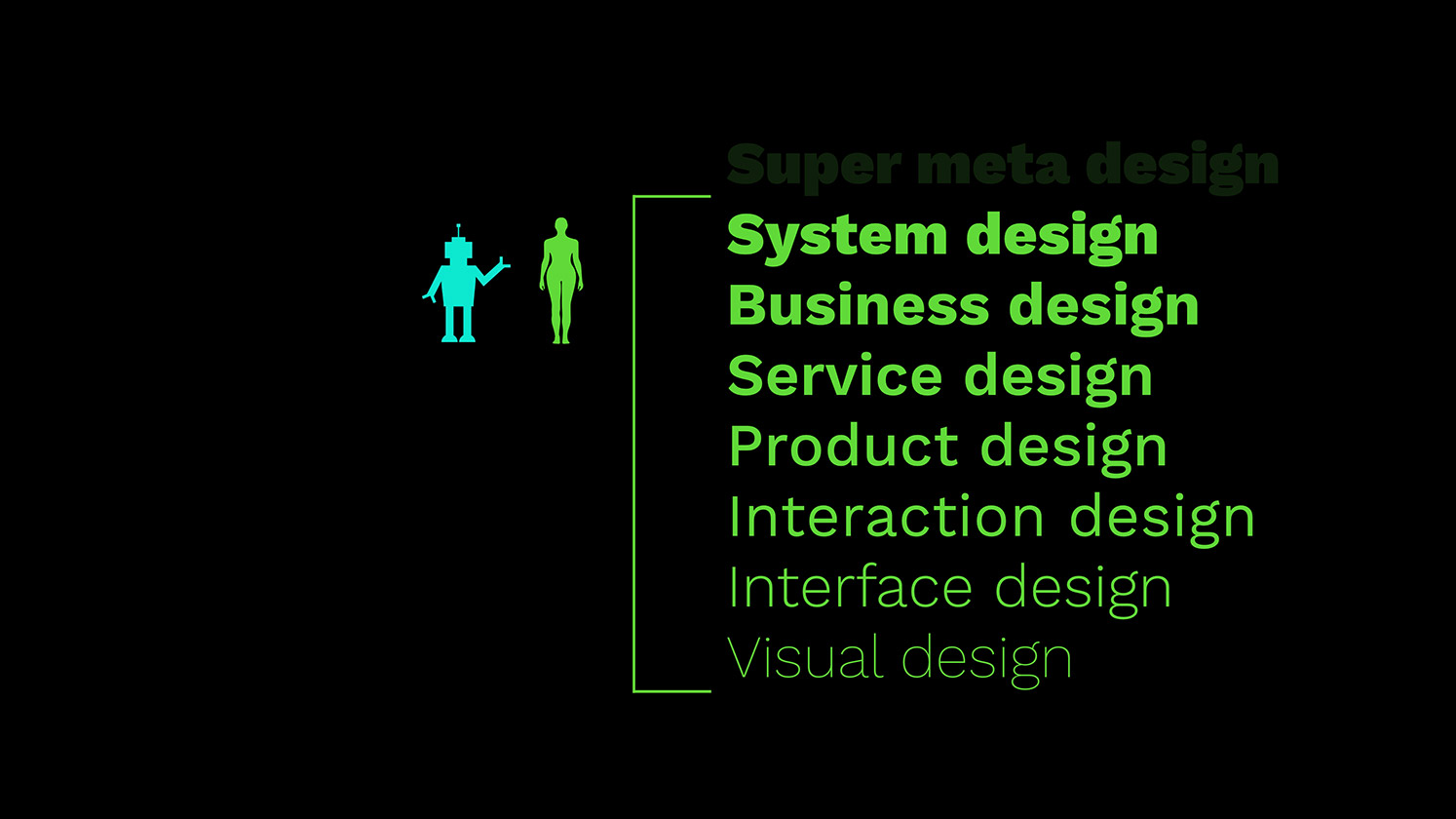

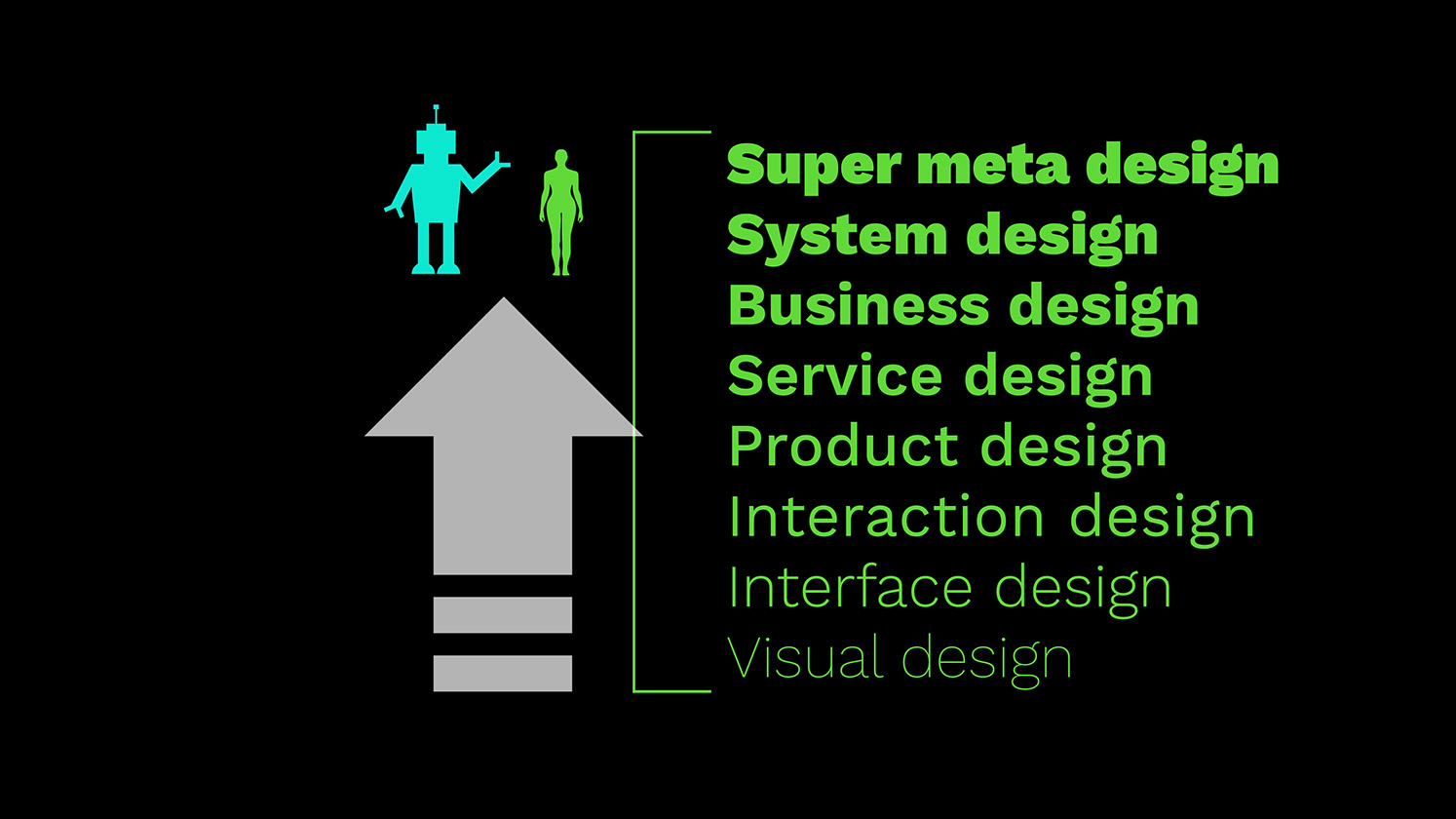

The good news is that we designers and creative thinkers are incredibly well positioned to lead the way forward. In just a few short years, we’ve started to climb this loose hierarchy of disciplines to gain real influence.

Our powerful tools and methods are helping us evolve from the atomized design of individual product experiences to the higher-level design of services, businesses and larger systems. Think smart cities or renewable energy and infrastructure.

I’m hugely optimistic that as data continues to expand our field of vision and technology amplifies our capabilities, we will begin designing solutions to some of the really big challenges…

…like fixing privacy…

…mitigating the most catastrophic effects of climate change…

…colonizing Mars so Matt Damon has some company up there,…

…becoming cyborgs,…

…building Dyson spheres,…

…and giving rise to the technological singularity by which point we won’t really be “we” anymore but a global superconscious “I.”

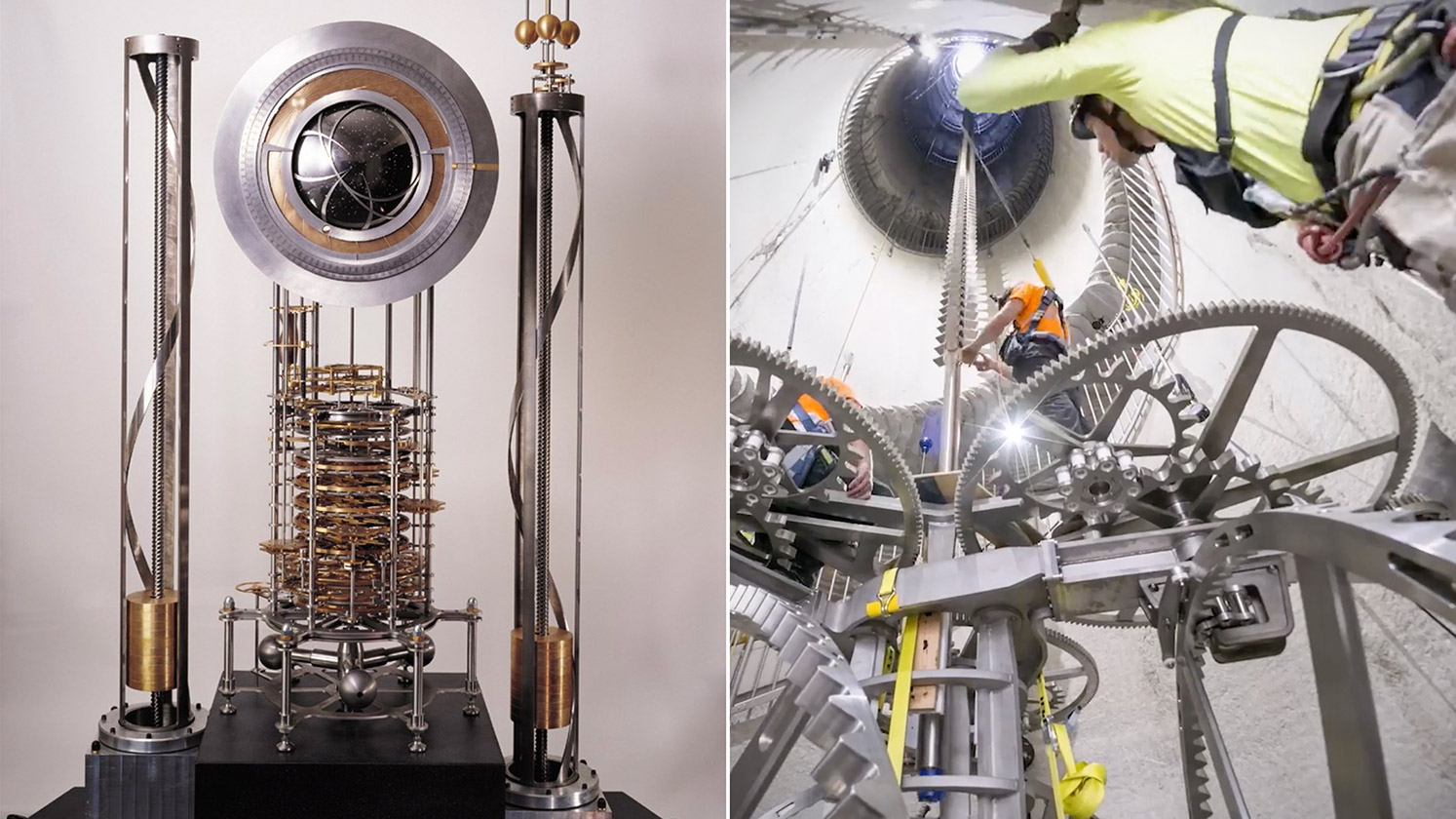

One last clock I’d like to mention is the clock of the Long Now. It’s being built right now inside a very solid mountain in Texas and it’s designed to run for 10,000 years.

Like Descartes’ metaphorical clock, this one helps us think differently. Unlike his clock, this one encourages us to zoom out and reflect on our actions in a much larger context.

So now we’ve answered our question. We’ve established that ninjas become knights and products become Homers because of Rene Descartes. 😉 Seriously though, it’s our golden age cognitive comfort zone and cultural mindset that allows local, rushed design decisions to pile up. In episode 75 of their Let’s Fix Things podcast, Joe and Guus at Raft Collective refer to this as “Digital litter.”

Over time we become used to the piles of litter because there’s seldom room in the budget or the schedule to truck them off and build a more elegant solution.

Complexity tends to be cumulative.

We’re getting really good at hiding the litter and complexity.

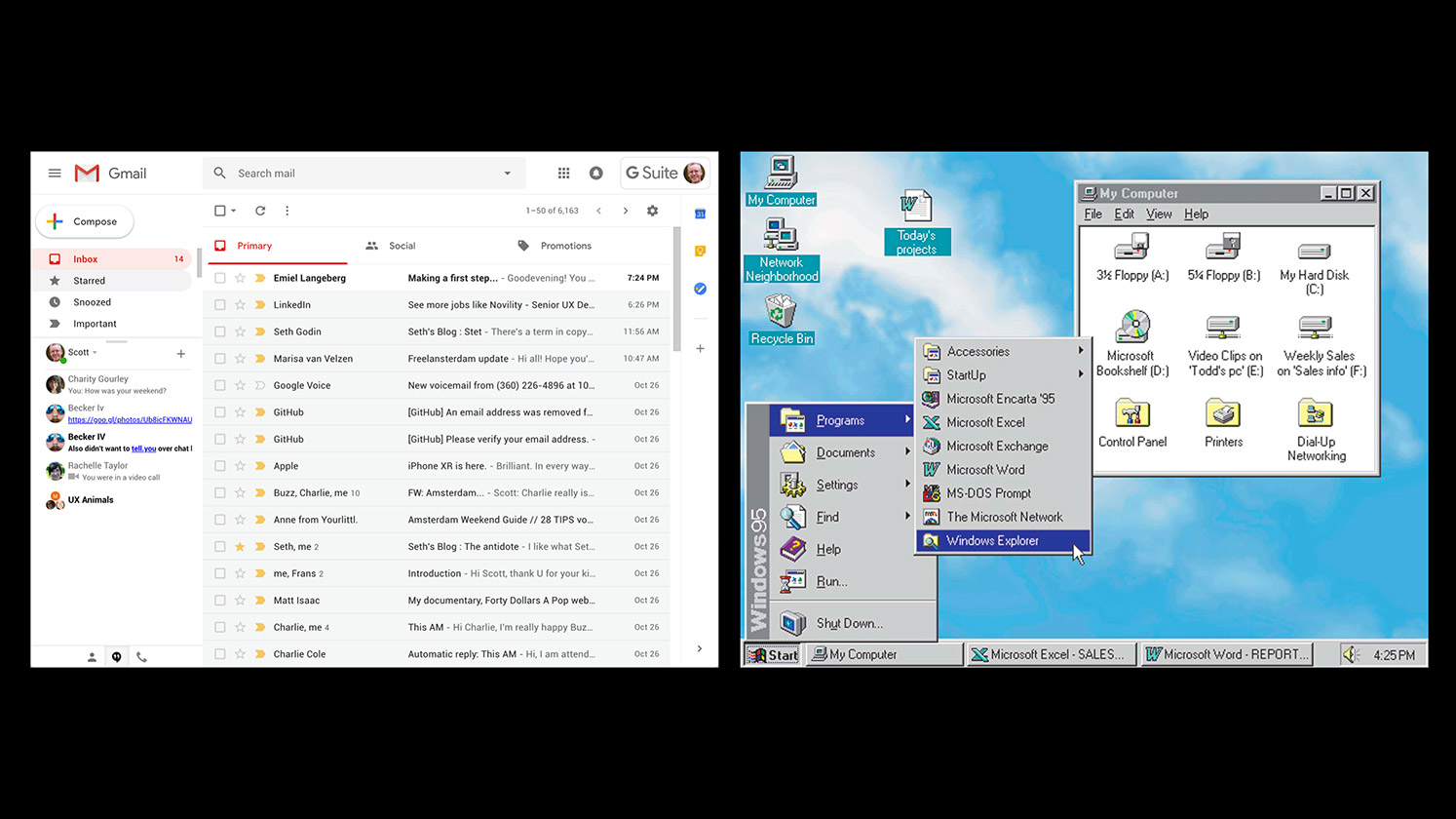

For another bit of perspective that kinda blew me away, consider the fact that loading Gmail in your browser invokes more storage and computing power than it took to run the entire Windows 95 operating system.

This popular quote from Twain points to the underlying challenge. As everything speeds up and we’re crunched for time, we’re writing longer and longer “letters.”

I believe that cultivating the discipline and making the time to write short letters will pay huge dividends over time.

No matter how fast we get at adding, iterating, and abstracting, doing something right will always be faster and more satisfying than doing it over.

And no, the irony of saying this on slide number 89 is not lost on me. 😉

One of the best ways I’ve found to cultivate that discipline is also one of the simplest.

Keep… asking… why? That one simple word cuts through assumptions like a sword through an enemy.

Many of us have heard of the 5 whys technique but bear with me here.

A customer asks you to sell them a drill bit and you ask:

"Why do you need a drill bit?"

They respond that they need to make some holes. You respond by asking:

"Why do you need holes?"

They answer, “Because I’m building some bookshelves.”

Ikea found an opportunity after just 2 whys but you keep asking:

"Why are you building bookshelves?"

They answer, “Because I have a lot of books to store” to which you respond:

"Why do you have so many books to store?"

They say “Because I haven’t read them all and I might want to re-read some of them later.”

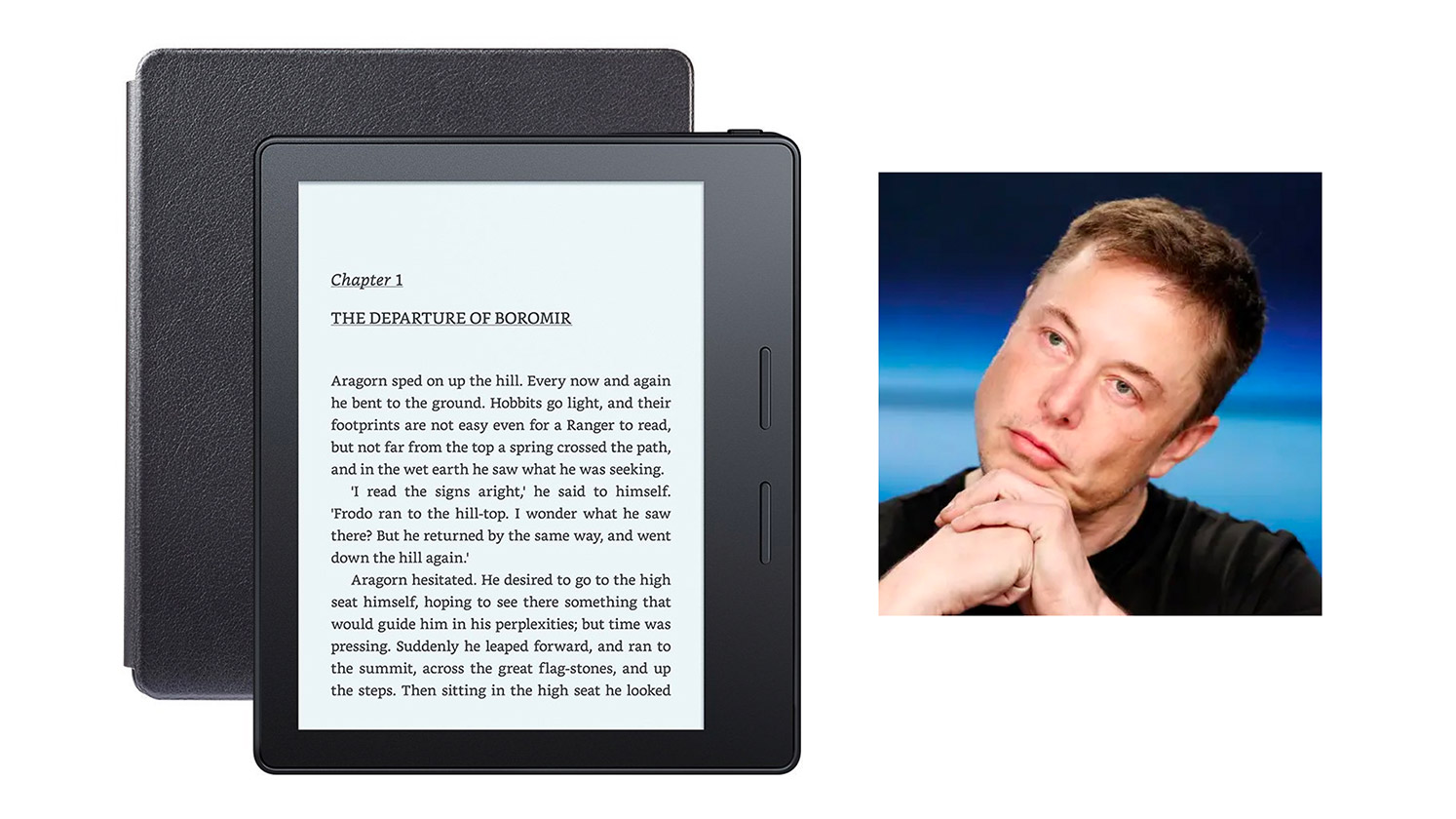

Amazon found another big opportunity at why number 4.

But not to be outdone by Jeff Bezos, Elon keeps going:

“Why do we have to read at all? Reading is a painfully slow way to get information into a brain.”

“Why can’t we be like Trinity in The Matrix…

…and learn how to fly a helicopter in a couple seconds?”

Yes, he’s really founded a company that’s working on this which is either incredible or incredibly terrifying.

Why is the fuel that propels us upward to higher-order design work.

I'll just put this here...

…and leave you with these simple take-aways.

Thanks for your time and attention tonight. I’d love to hear your thoughts about this talk or anything else related to design, creativity, technology, culture, etc. I’m always down to grab a coffee or a beer.